Mark Lynas joins the cottage industry of hating on Jared Diamond as he spins a myth of "

The myth of Easter Island's ecocide:"

Few historical tales of ecological collapse have achieved the cultural

resonance of that of Easter Island. In the conventional account, best

popularised by Jared Diamond in his 2005 book ‘Collapse’,

the islanders brought doom upon themselves by over-exploiting their

limited environment, thereby providing a compelling analogy for modern

times. Yet recent archaeological work suggests that the eco-collapse

hypothesis is almost certainly wrong – and that the truth is far more

shocking.

As we will see, the most "shocking" thing Lynas brings to bear is evidence of his own incompetence and/or malice in misrepresenting Diamond's argument in the measured, carefully argued

Collapse.

Judith Curry

spreads the meme, and extends the faulty argument:

[C]omplex coupled social-ecological-environmental systems, simple theories

are almost certain to be too simple. The complexity of such coupled

systems precludes simple cause-effect analyses. If we are arguing

about such a system on the scale of Easter Island, what hope do we have

of understanding and managing such interactions on continental or even

global scales? Ecosystems eventually adapt to climate change and

insults from humans.

From arguing that Diamond got Easter Island's tragedy wrong, Curry somehow gets to the point that all of Diamond's thinking is wrong, because it is "too simple," and by the way, climate science is impossible, because it is too simple too. Also, ecological devastation is nothing to worry about because "Ecosystems eventually adapt to climate change and insults from humans." (That single sentence is wrong in so many dimensions -- the moral, the practical, and the scientific -- not just Pollyannish but horribly pantheist and anti-humanist -- that it deserves its own post.)

|

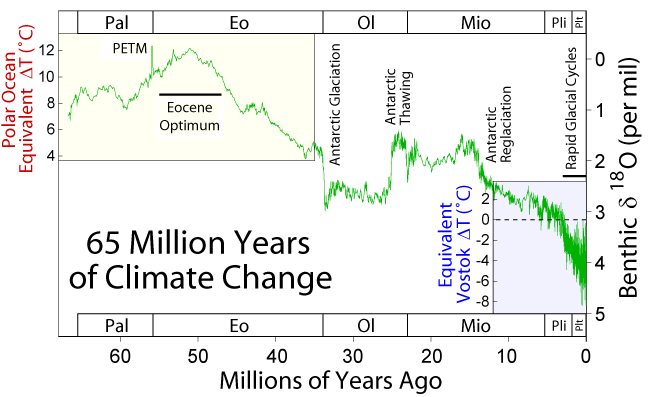

| Judith Curry was once a respected climate scientist. Now she poses for photos like this. |

But we should really start with patient zero, Lynas himself. The reality he is describing -- one historian has one idea about how something happened, supported by pieces of evidence, and other historians highlight new evidence that challenges that account -- is really not punchy enough for the kind of "gotcha" post Lynas is writing (those evil environmentalists are trying to scare you!). So he sexes up the allegations with a small army of straw men:

Diamond’s thesis is that the island’s original lush tree-cover was

destroyed by the Polynesian colonists, whose cult of making massive

statues (for which the island is now famous) required prodigious amounts

of wood to transport these huge rock idols. He suggests that as the

ecological crisis brought on by deforestation worsened, the islanders

tried to appease their apparently angry gods by making and transporting

yet more statues, creating a vicious circle of human stupidity.

Anybody who has spent five minutes paying attention to Jared Diamond would know that he would be highly unlikely refer to an entire culture's spiritual practices as a "cult." The only use of the word "cult" in the entire book refers to a post-disaster religious practice which Diamond regards positively: "The survivors adapted as best they could, both in their subsistence and in religion . . . the new religion developed its own art styles . . ." (141).

What about the vivid (and given Curry's reaction, unintentionally self-referential) phrase "a vicious circle of human stupidity"? Did Diamond say anything like that?

Actually, if you search Collapse for the word "stupid," you find the opposite -- Diamond stressing the intelligent and cultured native civilizations, whose behavior we unfairly judge, with the benefit of hindsight, to have been unintelligent:

Page 24: "The societies that ended up collapsing were (like the Maya) among the most creative and (for a time) advanced and successful of their times,

rather than stupid and primitive."

Page 513: "With the

gift of hindsight, we now view it as incredibly

stupid that colonists would release into Australia two alien mammals . . . But

it's still difficult for professional ecologists to predict which introductions . . . will prove disastrous. . . . Hence,

we really shouldn't be surprised."

Page 518: "We

unconsciously imagine . . . just a single tree left, which an islander proceeds to fell in

an act of incredible self-damaging stupidity. Much more likely, though,

the changes in the forest cover from year to year would have been almost undetectable . . ."

Whenever Diamond mentions stupidity (and there's one more reference, on page 624, but it's just the same) it is always to defend societies (and not just native societies; he sticks up for the Australian colonists too) from our harsh judgements,

with the benefit of hindsight, that they behaved stupidly.

This is incredibly obvious to anyone that has read any of Diamond's books, including his most famous book,

Guns, Germs, and Steel (and if you haven't read it, do). The theme that runs through all of Diamond's writing is that people are people and in the long-term make a similar proportion of good and bad decisions, decisions which however are usually based in a fairly deep understanding of the conditions in which the people at the time lived, decisions that are often smarter and more flexible than we tend to attribute to societies other than our own.

That is Diamond's big idea, and Lynas gets him entirely backwards. So how does he sell this straw man Diamond to the reader? Check out this epic bait and switch:

Diamond was not the first to draw this specific analogy: over a decade earlier, in a 1992 book entitled ‘Easter Island, Earth Island’, Paul Bahn and John Flenley (both palaeoecologists) wrote:

“…the person who felled the last tree could see that it

was the last tree. But he (or she) still felled it. This is what is so

worrying. Humankind’s covetousness is boundless. Its selfishness appears

to be genetically inborn. Selfishness leads to survival. Altruism leads

to death. The selfish gene wins. But in a limited ecosystem,

selfishness leads to increasing population imbalance, population crash,

and ultimately extinction.”

Lynas suggest that Diamond's thesis builds on this one, but as we now know, Diamond's conclusion was precisely the opposite:

“…

the person who felled the last tree could see that it

was the last tree. But he (or she) still felled it."

Page 518: "

We unconsciously imagine . . . just a single tree left, which an islander proceeds to fell in an act of incredible self-damaging stupidity. Much more likely, though, the changes in the forest cover from year to year would have been almost undetectable . . ."

Lynas depicts Diamond as extending the argument of Bahn and Flenley (doubtless the most extreme and unsupportable conclusion he could find) despite the fact that Diamond specifically addresses this theory and categorically refutes it. That's not just a poor argument: it's dishonest to attribute to Diamond a thesis he specifically entertained and vehemently rejected.

There's more here, much more, but after we've caught Lynas using

Collapse to attribute beliefs to Diamond which are exactly the opposite of what he wrote in

Collapse, that's sort of the end, isn't it? He's committed credibility suicide as that point. As so often with such as Lynas, we are left with the eternal question: is he a liar or just a sloppy incompetent?

UPDATE: Yes, I know I said that catching Lynas in a 180 degree misrepresentation of Diamond was enough to call it right there, but here's one more fun fact about his fallacy-laden screed.

Lynas casually introduces the following reference:

As Benny Peiser points out in this 2005 paper,

fish supplies were abundant, and reports from early European explorers

that the islanders were thin and miserable-looking are highly

contradictory (others report that they lived in comparative luxury).

Certainly Diamond’s reading of this seems highly partisan. As Peiser

puts it:

“Together with abundant and virtually unlimited sources

of seafood, the cultivation of the island’s fertile soil could easily

sustain many thousands of inhabitants interminably. In view of the

profusion of broadly unlimited food supplies (which also included

abundant chickens, their eggs and the islands innumerable rats, a

culinary ‘delicacy’ that were always available in abundance), Diamond’s

notion that the natives resorted to cannibalism as a result of

catastrophic mass starvation is palpably absurd. In fact, there is no

archaeological evidence whatsoever for either starvation or

cannibalism.”

Sounds bad for Diamond. I'll just do a quick check, as I always do, to make sure this paper is good science by a respected author in a reputable peer-reviewed journal . . .

B. Peiser (2005) From Genocide to Ecocide: The Rape of Rapa Nui Energy & Environment volume 16 No. 3&4 2005

Energy and Environment. Your source for all your archaeological and archaeometrical needs, without the stress and hassle of peer review. So, Mr. Peiser, how did you come to be publishing in such as illustrious pillar of the historical sciences?

Of course there's a Sourcewatch page:

Benny Peiser is a UK social anthropologist on the Heartland Institute "Global warming experts" list. He runs CCNet (network) and is frequently quoted in Local Transport Today, a transport journal that frequently features the views of climate change skeptics. He is director of the Global Warming Policy Foundation.[1] He is co-editor of the skeptic journal Energy and Environment[2] and is on the editorial board of the Electronic Journal of Sustainable Development.

An expert in climate change

and historical instances of Polynesian cannibalism. Talk about your double threats.

His educational background is not given . . . I'm sure we can all come to a reasonable inference about that. But he is (or was) an academic, to be sure:

Senior Lecturer in Social Anthropology & Sport Sociology, Liverpool John Moores University

So far Mark Lynas has promoted this clown, and Judith Curry repeats the quote, whilst praising Lynas' "opening mind." Who will be next to join them in embarrassing themselves with lavish praise for psuedoscience? This threatens to become the Jonestown of credibility suicides.